For a budding and even for a seasoned researcher, nothing is more rewarding than to have one’s publications cited. Sometimes that happens in the unlikeliest of places. Or maybe this place is not so unlikely after all, given the main themes of my 10 years of research: supply chain risk, business continuity, and transportation vulnerability. It’s the latter that has caught the attention of a consultancy in the UK when preparing a report for the UK Highways Agency. The report, dated 2010 and titled Network Resilience and Adaptation, assesses and details in great depth the vulnerability and resilience of the transport infrastructure in the East of England and displays it using a GIS. “My” contribution, if I may call it that, is in the literature review section of the report, where definitions and perspectives on vulnerability, resilience and related terms are discussed. Frankly, I had almost forgotten about these definitions, since I wrote them in a paper in 2004, but it’s nice to see that they still make an impact.

For a budding and even for a seasoned researcher, nothing is more rewarding than to have one’s publications cited. Sometimes that happens in the unlikeliest of places. Or maybe this place is not so unlikely after all, given the main themes of my 10 years of research: supply chain risk, business continuity, and transportation vulnerability. It’s the latter that has caught the attention of a consultancy in the UK when preparing a report for the UK Highways Agency. The report, dated 2010 and titled Network Resilience and Adaptation, assesses and details in great depth the vulnerability and resilience of the transport infrastructure in the East of England and displays it using a GIS. “My” contribution, if I may call it that, is in the literature review section of the report, where definitions and perspectives on vulnerability, resilience and related terms are discussed. Frankly, I had almost forgotten about these definitions, since I wrote them in a paper in 2004, but it’s nice to see that they still make an impact.

Publish or perish

I guess the old academic adage of “publish or perish” still holds true, although some appear to perish despite the publish, as I have written about before, in my post on the Catch 22 of academic publishing. Obviously, fame doesn’t come instantly, but good things come to those who wait. In this case it was Christopher Mason of Hyder Consulting who dug up what I had done and published, and almost forgotten, so I guess I owe Chris a big one for not letting me perish.

My favorite

Christopher didn’t just dig me up. His main literature source is actually one of my favorites when it comes to transportation vulnerability, it’s Katja Berdica’s 2002 article on road vulnerability, the paper that got me started in this direction and that I reviewed on this blog some time ago.

Terms and definitions

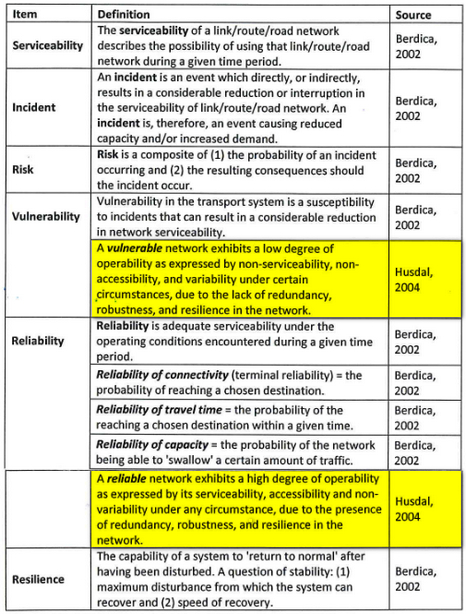

In the report, Mason lists the different terms and definitions that Berdica and I use in our approaches towards vulnerability:

Looking back it’s interesting how I defined reliable as able to operate under any circumstance, while I saw vulnerable as not able to operate under certain circumstances. Not a very sophisticated definition, I must admit that, but it did the trick, apparently.

Shocks aka risks aka vulnerabilities

While Berdica sort of has the upper hand on the definitions, when it comes to what can affect transportation networks adversely, Mason uses my three types of risks and adds a forth type of accidents and attacks:

- Structure-related (the way the transport network is built and the attributes of the network itself, its physical characteristics such as geometry, width, curvature, gradient, weight restrictions, height restrictions, presence of bridges, tunnels)

- Nature-related (topography and the terrain the road traverses and natural incidents such as floods, snow, ice, fog, climate change and so on)

- Traffic-related (traffic flow and attributes causing change such as peak periods, special events, maintenance operations, accidents)

- Other (terrorism, international events, protests, industrial incidents)

The fourth “shock” as Mason calls it, was added in by him, while the first three are taken directly from a paper I presented at three different conferences in late 2004 and early 2005. Said paper was titled reliability and vulnerability versus benefits and costs and discussed the notion that reliability and vulnerability apparently do play a major role in transportation, yet are seemingly omitted from cost-benefit analyses of transportation projects, something I intended to rectify in my research. I never did, but that’s another story. That said, Mason makes extensive use of my three categories of risks together with his fourth category in determining the transportation hazards that the UK road network may be exposed to.

Resilience factors

Another interesting takeaway from Mason’s report are the 10 factor’s that make up transportation resilience, taken from a 2006 article by Pamela Murray-Tuite:

- Redundancy – the transport system contains a number of functionally similar components which can serve the same purpose and hence the system does not fail when one component fails (for example, a number of similar routes are available with spare capacity).

- Diversity – the transport system contains a number of functionally different components in order to protect the system against various threats (for example, alternative modes of transport are available).

- Environmental Efficiency – a transport system which is environmentally efficient will be more sustainable, and capacity is less likely to be constrained due to environmental reasons.

- Autonomy – the components of the transport system are able to operate independently so that the failure of one component does not cause others to fail (for example, can the transport system operate safely in the event of a power cut?).

- Strength – the transport systems ability to withstand an incident (for example, how extreme a flood event can the system cope with?).

- Adaptability – or flexibility, can the transport system adapt to change and does it have the capacity to learn from experience (for example, an area-wide traffic management system can adapt to differing traffic conditions).

- Collaboration – information and resources are shared among components and/or stakeholders (for example, contingency plans in the event of an emergency and the ability to communicate with system users).

- Mobility – travellers are able to reach their chosen destinations at an acceptable level of service.

- Safety – the transport system does not harm its users or expose them, unduly, to hazards.

- Recovery – the transport system has the ability to recover quickly to an acceptable level of service with minimal outside assistance after an incident occurs.

Compare these to the resilience taxonomy developed by Andrew Cox et al. (2011). That is a very different picture, but there are still many commonalities. Personally, I prefer this framework here. Mason uses these factors to identify and map vulnerabilities and hotspots in the transportation network, and I am really impressed by the level of detail in the report.

Google Scholar

I would never have known about my rise to fame were it not for that I from time to time use Google Scholar to check for articles referencing my works. I like Google Scholar, because it gives me a much wider range of results, as already noted by Howland et al. (2009). I must admit that I do like to see who uses what parts of my work and where. Firstly, because I may find further ideas for expanding my work, based on what others have done with it. Secondly, because I may find more people to connect with, and many of my LinkedIn connections were made after “stumbling upon myself “, so to speak.

Reference

Mason, C. (2010) Network Resilience and Adaptation – Phase 1 Final Report. Report no. 3003-GD31094-GDF-02, Hyder Consulting.

Author link

- linkedin.com: Christopher Mason

Related link

- hyderconsulting.com: “Outstanding people – exceptional solutions”

Download

- husdal.com: Literature review (4 pages from the above report)

Related posts

- husdal.com: Reliability and vulnerability versus costs and benefits

- husdal.com: Road vulnerability as defined by Berdica