Supply chain collaboration, easy or difficult? And can it really work? In theory yes, but in reality? Maybe not. While supply chain collaboration has been hailed by many as the way to improve supply chain performance, more often than not supply chain partnerships fails miserably, because the required prerequisites are not met by the companies involved. Obviously, collaborations that fail can be an unexpected major supply chain risk, or perhaps it should have been foreseen? In their 2006 article Realities of supply chain collaboration, R. Kampstra, J. Ashayeri, & J. Gattorna aim to investigate the gap between the interests in supply chain collaboration and the relatively few recorded cases of successful applications. In the end they develop a framework for what it takes to make collaboration work in supply chains.

Supply chain collaboration, easy or difficult? And can it really work? In theory yes, but in reality? Maybe not. While supply chain collaboration has been hailed by many as the way to improve supply chain performance, more often than not supply chain partnerships fails miserably, because the required prerequisites are not met by the companies involved. Obviously, collaborations that fail can be an unexpected major supply chain risk, or perhaps it should have been foreseen? In their 2006 article Realities of supply chain collaboration, R. Kampstra, J. Ashayeri, & J. Gattorna aim to investigate the gap between the interests in supply chain collaboration and the relatively few recorded cases of successful applications. In the end they develop a framework for what it takes to make collaboration work in supply chains.

Many thoughts, one framework

The article approaches supply chain collaboration from a wide range of perspectives , in particular: the theory of constraints, and brings together many thoughts and ideas on how to collaborate and partner in a supply chain, and synthesizes these ideas into one interconnected framework that fully describes the inner workings of relationships in supply chains.

The key to achieving improved relationships will come through better understanding the ways that entities in supply chains work together.

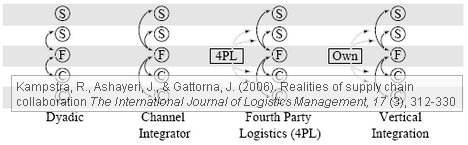

First the authors define supply chain collaboration as one of many forms of linkages in the supply chain: 1) arm’s length, 2) collaboration, 3) partnerhsip, 4) joint venture and 5) vertical integration:

Arm’s length relationships are purely transactional without any collaboration, while partnerships are a special case of collaboration, and where joint ventures have transcended from collaboration into an extended linkage beyond collaboration. Vertically integrated supply chain actors no longer collaborate (pun intended), but act as one.

Then they define some of the approaches to supply chain collaboration: 1) dyadic, 2) channel integrator, 3) Fourth party logistics (4PL) and 4) vertical integration, which signifies the deepest relationship.

Collaboration: a matter of cost and benefit?

Supply chain collaboration is immensely popular both in business and academia, but paradoxically, most collaborative initiatives end up in failure. Why?

- No equality between partners

- one dominates the other(s)

- Hampered by constraints

- resources, policies or potential market outreach

- Only potentially collaborative

- only if approached the right way

- Imbalanced priorities

- short-term local cost-savings come before long-term overall effectiveness

A true collaboration is more than two or more entities working together. A true collaboration must be accompanied by a fundamental change in thinking, otherwise it will not succeed.

Collaboration: three loops

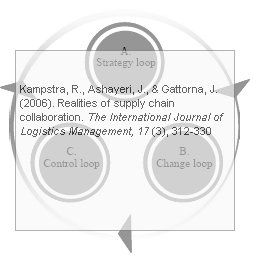

Collaboration involves constant change and alignment, time and again, something the authors illustrate using what they call the three loops of supply chain collaboration: 1) strategy, 2) change and 3) control.

The strategy loop involves 1) choosing strategic partners, 2) Identifying the appropriate supply chain strategy and 3) Aligning with the over overall corporate strategy for each potential relationship. The change loop consists of looking closer at reach relationship and then deciding 1) which entities that should change and 2) what that should change. The control loop governs and control the collaboration, as in 1) the transformational changes, and 2) the strategic objectives, and 3) by allocating benefits and burdens among the parties involved.

Buying behavior versus supply path

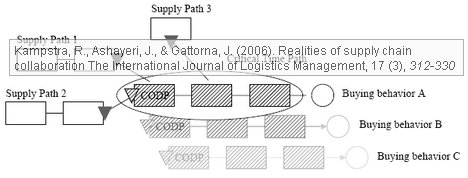

In his book on Dynamic Supply Chain Alignment, John Gattorna identifies four types of supply chains, based on four types of customer behavior. This notion is present also in this paper, where, each buying behavior must be aligned with the matching supply path, creating a critical time path from supplier to customer, based on the CODP:

Here the authors say that

There are three types of capacities to be set: productive capacity to meet demand; capacity to protect against statistical fluctuation of the process; and excess capacity for quickly adapting to customer dynamics.

This leads to a focus on 1) supply chain design and 2) supply chain coordination.

Supply chain design: the locations, number, and the size of supply chain entities, where the right capacities and buffers should be positioned.

Supply chain coordination: risk control, production policies, replenishment policies and distribution policies.

With all this in place, supply chain collaboration is possible.

Levels of collaboration

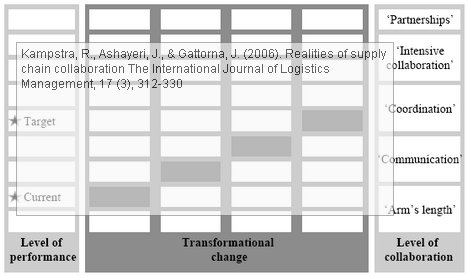

Base don the above mentioned loops of collaboration implying a step-wise improvement of supply chain performance through collaboration the authors come up with a concept they call “the ladder of collaboration”:

The initial level of collaboration is “Communication” assuming there is no starting collaboration. The second level of collaboration is “Coordination,” which focuses on the coordination of intra- and inter-entity processes. The third level of collaboration is “Intensive collaboration,” which implies increased involvement of the collaboration members to improve the strategic management decision-making and enhance innovation in the chain. The fourth level of collaboration is “Partnerships,” which involves extended financial linkages, such as sharing of investments and profits.

I believe that one of the reasons that supply chain collaborations fail is that the collaborating parties want too much too fast, without fully engaging in a stepwise alignment.

Why do collaborations fail?

In summary, this is why collaborations don’t always work out as intended:

- Collaboration comes in many formats and will and should depend on the contextual situation.

- At some point in the collaboration the group will face a supply chain constraint that limits further collaboration.

- Supply chains or channels are not necessarily all collaborative, some are better left as is.

- Collaboration ends up in failure when the start is all wrong and when compromises cover irreconcilable differences.

Sidekick: Coperative strategy

According one of best books I have seen on this topic, Cooperative Strategy by Child, Faulkner, & Tallman (2005), traditional enterprises can enter into various forms of cooperation for a number of reasons: 1) certainty – by developing relationships , 2) flexibility – by being able to quickly allocate a range of resources, 3) capacity – by “outsourcing” work to other network members, 4) speed – by being able to quickly respond to a wide range of business opportunities, 5) skills and competence – by gaining access to resources other than one’s own, and 6) intelligence – by sharing market information. Placing cooperative networks on a scale, going from independent to integrated, five degrees of networks can be discerned: 1) Equal-partner network, 2) Unilateral agreements, 3) Dominated network, 4) Virtual corporation, and 5) Strategic alliance. This arrangement is not unlike the framework proposed by Kampstra, Ashayeri, & Gattorna, perhaps a sign of universal applicability of the model?

Sidekick: Roles in collaboration

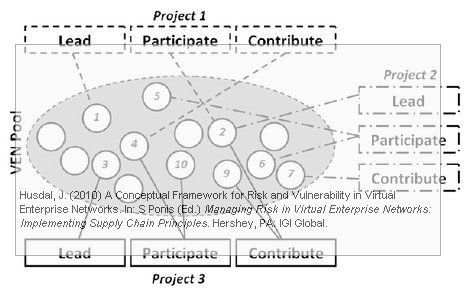

The paper makes a point that supply chain collaboration implies that the parties involved establish roles as to who should manage and/or coordinate the collaboration efforts. Interestingly, their framework is very similar to the one I used in my book chapter on a conceptual framework for risk and vulnerability in virtual enterprise networks:

It’s funny, because I never thought of scouring the literature on supply chain collaboration when I wrote that chapter. had I done, I most certainly would have found and used this paper.

Critique

This paper is ripe with SCM acronyms, oops, I meant Supply Chain Management acronyms. Most of them are explained, but a couple are not. For example, take a look at the supply-path-buyer-behavior-figure above…what is that CODP? While not explained in the paper, I assume it relates to Customer Order Decoupling Point. Another not explained acronym used in the paper is DIFOT, presumed to mean Delivered In Full, On Time. Perhaps the authors, very familiar with these terms, asume that their readers are too? It’s a small glitch, but n annoying glitch, when you are trying to understand this paper. That said, I have seen far worse glitches in editorial review than this one.

Reference

Kampstra, R., Ashayeri, J., & Gattorna, J. (2006). Realities of supply chain collaboration The International Journal of Logistics Management, 17 (3), 312-330 DOI: 10.1108/09574090610717509

Author links

- johngattorna.com: John Gattorna

- tilburguniversity.nl: J AShayeri

- unknown: R.P. Kampstra

Related

- husdal.com: Dynamic Supply Chain Alignment

- husdal.com: Cooperative strategy